🚄 Reaching 80MHz

One of the key design goal of periph.io is to be as fast as possible while exposing a simple API. For GPIO pins, this means having reliable low latency in the happy path.

In this article, we’ll describe how we:

- wrote a reproducible benchmark for GPIO that can be used across platforms, which measures output performance by toggling the output low and high continuously as fast as possible ⎍⎍⎍⎍ and for input performance by, unsurprisingly, reading continuously

- optimized outputs and inputs against the benchmarks

- determined incorrect optimizations and benchmarking issues

- determined performance anti-patterns

Are we fast yet?

Use case

Why micro-optimize the GPIO to be as fast as possible? Use cases include:

- Bit banging, which can be used to emulate a protocol.

- Software based PWM or Servo.

- Software-based best-effort logic analyzer.

- Using as little CPU overhead for devices on CPU bound operation especially in the case of single-core platforms like the Raspberry Pi Zero and the C.H.I.P.

Overall Methodology

I took measurements via periph-smoketest, which leverages the excellent benchmarking support in package testing from the Go standard library.

All builds were done with Go 1.9.2.

3 boards are tested:

- C.H.I.P., both with a native GPIO and a XIO-Pn GPIO (CSID0/PE4/132 and XIO-P0/1013 were used)

- Raspberry Pi 3 running Stretch Lite (GPIO12 was used)

- Raspberry Pi Zero Wireless running Stretch Lite (GPIO12 was used)

3 drivers are tested:

- sysfs, available on all linux platforms.

- CPU specific drivers which leverage memory mapped CPU registers to bypass the kernel:

The command used was one of the following based on the driver being tested, and

NN being the GPIO number:

periph-smoketest allwinner-benchmark -p NN

periph-smoketest bcm283x-benchmark -p NN

periph-smoketest sysfs-benchmark -p NN

Optimizing Output

Methodology

The basic output benchmark creates a clock, toggles the output between gpio.High and gpio.Low as fast as possible, e.g. ⎍⎍⎍⎍ . It counts the number of individual sample, not the generated clock rate. The generated clock is half of the rate printed out.

p := s.p

if err := p.Out(gpio.Low); err != nil {

b.Fatal(err)

}

n := (b.N + 1) / 2

b.ResetTimer()

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

p.Out(gpio.High)

p.Out(gpio.Low)

}

Initial Results

The initial results weren’t really good 🐢, but gave a starting point. I (Marc-Antoine) had tried to make the code fast simply by designing with “performance in mind” but up to now the optimization process had been done completely blind, as no performance testing was being done.

| C.H.I.P. XIO | C.H.I.P. GPIO | RPi3 | RPiZW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sysfs | 4.0kHz | 97kHz | 153kHz | 47kHz |

| CPU driver | N/A ¹ | 989kHz | 3.3MHz | 3.4MHz |

¹ The XIO pin on the C.H.I.P. is provided on the header via an external PCF8574A chip connected over I²C, so the CPU driver cannot be used to control it.

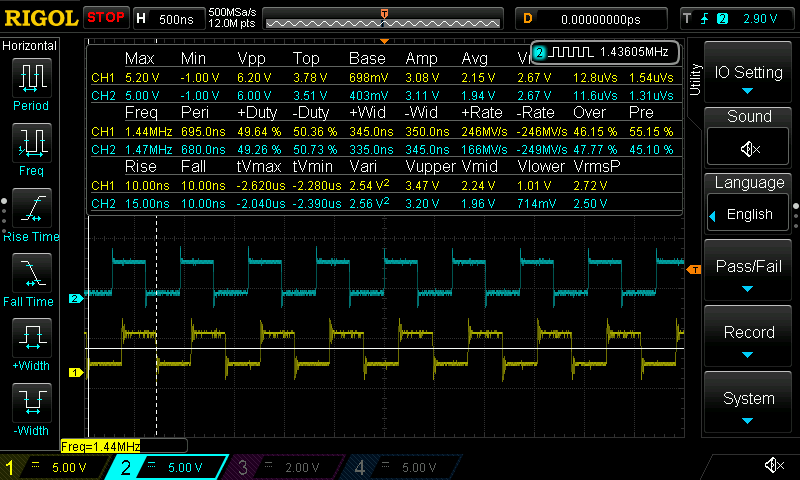

Screenshot of a slower run of bcm283x-benchmark with two boards running the benchmark simultaneously:

It works! Blue is RPi3, yellow is RPiZW

Observations

- The CPU drivers were definitely slower than what could be achieved by an order of magnitude.

- Using sysfs driver incurs a cost between 10x to 72x (!) in terms of performance.

- The sysfs driver is significantly slower on the RPiZW than the RPi3 for an unknown reason. Even the CHIP is faster.

- The C.H.I.P. with the CPU driver is 3.5 times slower than a Raspberry Pi Zero Wireless even with the same clock speed (1GHz).

- The XIO-Px pins on the C.H.I.P. are very slow due to the I²C communication overhead. These should only be used for signals that changes infrequently, e.g. driving a LED. It is has the capacity to directly drive LEDs up to 25mA, unlike the CPU GPIOs.

1st optimization: Bounds checking

The first fix was to reduce the overhead due to Go’s bound checking code. This was done by:

- allwinner: use explicit switch

case for allwinner to expand the indexes

[1]to[7]instead of[p.group]in commit 8ce90f7a25. - bcm283x: use explicit index

[0]and[1]instead of[p.number / 32]in commit a929d4be37.

| C.H.I.P. GPIO | RPi3 | RPiZW | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU driver (before) | 989kHz | 3.3MHz | 3.4MHz |

| CPU driver (after) | 1.1MHz | 3.9MHz | 3.4MHz |

This is a good improvement with a simple change. Boundary checks in Go cost a lot, so for performance sensitive code, it is worth doing micro benchmarks to determine if tweaks can be done to reduce the cost.

A notorious example is the binary package in the standard library.

2nd optimization: Cutting out the safety

To get further into deep performance, the safety checks in Out() need to be

removed to reduce the number of branches in the hot path. This was done by

adding a new function FastOut() that skips all the safety checks. Out() does

the safety checks, then calls FastOut().

This is symmetric to input operation via In() then Read().

This was done with minimal API increase with a single new function via commits ee4d184ee2 for allwinner and 104d587821 for bcm283x.

| C.H.I.P. GPIO | RPi3 | RPiZW | |

|---|---|---|---|

Out() | 1.1MHz | 3.9MHz | 3.4MHz |

FastOut() | 4.6MHz | 82.6MHz | 29.3MHz |

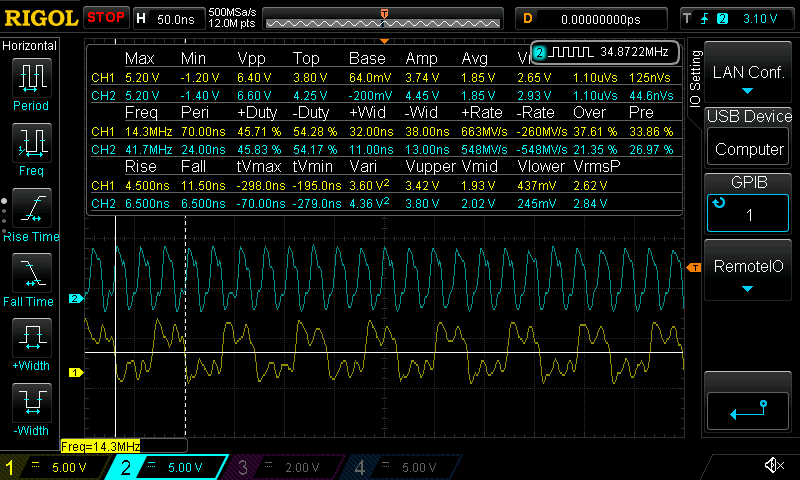

Now we’re talking! 82.6MHz for the RPi3, and the C.H.I.P. is now in the higher MHz range. In fact, this is so fast on the RPis that my oscilloscope has a hard time getting a clear signal:

« I'll need a bigger oscilloscope »

There’s also a risk that the signal integrity at this point can just not be guaranteed with the GPIO so you will need to plan the electric properties of the design accordingly.

Keep in mind the risk of using FastOut(): you must assert that Out()

succeeded before and that no other call was done, like when using Read().

Failed optimizations

I also tried two optimizations that lead to dead paths.

First was to inline the gpio.Level

argument, creating one dedicated function per level: FastOutLow() and

FastOutHigh(). This doesn’t significantly affect the performance on the RPi3

but does give a 18% performance boost on the RPiZW on the micro benchmark. In

practice, this “optimization” would make the call sites trickier when the level

is not known in advance (hard coded) so this was left out.

Second, if you take a look at the bcm238x FastOut() implementation, you may be

tempted to hardcode the bit mask used to set the CPU register. In practice this

didn’t affect the performance at all.

Optimizing Input

So we optimized Out() and created a fast path function FastOut(). What about

input now?

Methodology

Similar to output, input latency needs to be consistently measured. The first

step is to create the benchmark and run it on platforms. It is called InNaive

in the periph-smoketest benchmarks.

p := s.p

if err := p.In(gpio.PullDown, gpio.NoEdge); err != nil {

b.Fatal(err)

}

b.ResetTimer()

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

p.Read()

}

Initial Results

| C.H.I.P. XIO | C.H.I.P. GPIO | RPi3 | RPiZW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sysfs | 3.8kHz | 79.4kHz | 139kHz | 41.9kHz |

| CPU driver | N/A ¹ | 66.6Mhz | 70MHz | 41MHz |

¹ As noted for output testing, XIO pins are only accessible via sysfs.

Clearly, the input code is fairly performant! The C.H.I.P. even outperforms the RPiZW by a wide margin.

So we can leave it at this?

Right?

Fast benchmarks, and lies

But what is the data measured above was a complete lie? Remember that the SSA optimizer can optimize across concrete calls, so if a value read is never used, the read operation may be optimized out. To ensure this is true, we change the micro benchmark from the version above to:

p := s.p

if err := p.In(gpio.PullDown, gpio.NoEdge); err != nil {

b.Fatal(err)

}

l := gpio.Low

b.ResetTimer()

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

l = p.Read()

}

b.StopTimer()

b.Log(l)

and here’s the results:

| C.H.I.P. GPIO | RPi3 | RPiZW | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU driver (lie) | 66.6Mhz | 70MHz | 41MHz |

| CPU driver (real) | 8.9MHz | 10.7MHz | 12.3MHz |

Ouch! That hurts. This proves that the naive benchmark wasn’t testing much at all, and it is important to trick the SSA optimizer into not optimizing too much.

Optimization attempts

The Ugly

The input code on bcm283x looks like this:

func (p *Pin) Read() gpio.Level {

if gpioMemory == nil {

return gpio.Low

}

return gpio.Level((gpioMemory.level[p.number/32] & (1 << uint(p.number&31))) != 0)

}

One would be tempted to do, similar to FastOut(), skip the gpioMemory == nil

check to shorten it as one line:

func (p *Pin) FastRead() gpio.Level {

return gpio.Level((gpioMemory.level[p.number/32] & (1 << uint(p.number&31))) != 0)

}

Interestingly, this code is slower, and not just a bit, it’s 2x slower. So in Go, it’s sometimes important to keep these checks, to prove to the compiler that the code cannot panic.

The Bad

Wait a minute! FastOut() doesn’t have the check for gpioMemory == nil. What

happens if it is added?

The funny thing is that FastOut() becomes ~2% faster on the RPi3 and ~2%

slower on the RPiZW, so it was not added. Likely worth exploring one day.

The Good

On the other hand, the same indexing hardcoding done for writing can be leveraged as done in commit a8f6613d5f for bcm283x. It was tried for the C.H.I.P. but as you can see below, it didn’t affect performance at all so this change was never committed.

| C.H.I.P. GPIO | RPi3 | RPiZW | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU driver (before) | 8.9MHz | 10.7MHz | 12.3MHz |

| CPU driver (after) | 8.9MHz | 11.3MHz | 13.6MHz |

Expanding the switch case on the C.H.I.P. has no measurable effect, but it gives a 7%~10% performance boost on the RPi3, which is significant.

Loops vs Unrolling

Look at these two snippets and try to guess which one is the fastest:

Pattern #1:

p := s.p

if err := p.In(gpio.PullDown, gpio.NoEdge); err != nil {

b.Fatal(err)

}

l := gpio.Low

b.ResetTimer()

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

l = p.Read()

}

b.StopTimer()

b.Log(l)

Pattern #2:

p := s.p

if err := p.In(s.pull, gpio.NoEdge); err != nil {

b.Fatal(err)

}

buf := make(gpiostream.BitsLSB, (b.N+7)/8)

b.ResetTimer()

for i := range buf {

l := byte(0)

if p.Read() {

l |= 0x01

}

if p.Read() {

l |= 0x02

}

if p.Read() {

l |= 0x04

}

if p.Read() {

l |= 0x08

}

if p.Read() {

l |= 0x10

}

if p.Read() {

l |= 0x20

}

if p.Read() {

l |= 0x40

}

if p.Read() {

l |= 0x80

}

buf[i] = l

}

b.StopTimer()

Tricky, eh?

#1 is effectively discarding all values but the last one while #2 is doing what we call an loop unrolling and storing the data into a slice, which means much more memory accesses and potential CPU cache trashing.

Yet, #2 is consistently as fast or faster than #1 on all platforms.

In general, doing explicit loop unroll is beneficial, but not always. It is worth carefully benchmarking first.

Performance anti-patterns

While doing research for this article, two performance anti-patterns came up

that are worth calling out. In the benchmarks, they are named

FastOutInterface and FastOutMemberVariabl in the periph-smoketest

benchmarks.

Anti-pattern: interface

Astute readers will notice that there is no interface in the package

gpio declaring the function FastOut().

A user may be tempted to do something like this:

type fastOuter interface {

Out(l gpio.Level) error

FastOut(l gpio.Level)

}

var p fastOuter = gpioreg.ByName("GPIO12")

p.Out(gpio.Low)

p.FastOut(gpio.High)

...

Don’t! At least, don’t without testing the performance implications. This lowers the performance on a RPi3 by 60%! This is a dramatic performance decrease, so it is very important to keep the code to only do concrete direct calls and not use an interface.

Generalizing: when calling a function more than a million times per second, it is likely worth making the call site a concrete call instead of an indirection through an interface. But this is not always the case, this has absolutely no impact on the C.H.I.P. benchmarks.

This also applies to using gpio.PinIn when using Read() in an high

performance loop. It may be worth doing a type switch to determine the underlying concrete

type to do static call whenever possible.

Anti-pattern: indirection

You may have noticed that the benchmark starts with:

p := s.p

because benchmarking struct has *Pin as a member p. This could be

simplified by using s.p everywhere in the benchmark function.

In practice, using an indirect variable slows down the performance

significantly for hot paths, for example FastOut() performances lowered on the

Raspberry Pi 3 by 15%. While this is not as bad as using an interface, it

significantly hurt performance and a local variable should be used for very

hot code paths.

Summary of results

Here’s the full results on a Raspberry Pi 3. The code used is in the bcm283xsmoketest/ directory.

$ periph-smoketest bcm283x-benchmark -p 12

InNaive 200000000 8.36 ns/op 119.7MHz

InDiscard 20000000 70.2 ns/op 14.3MHz

InSliceLevel 20000000 71.6 ns/op 14.0MHz

InBitsLSBLoop 20000000 70.4 ns/op 14.2MHz

InBitsMSBLoop 20000000 70.5 ns/op 14.2MHz

InBitsLSBUnroll 20000000 65.0 ns/op 15.4MHz

InBitsMSBUnroll 20000000 64.8 ns/op 15.4MHz

OutClock 10000000 223 ns/op 4.5MHz

OutSliceLevel 10000000 227 ns/op 4.4MHz

OutBitsLSBLoop 10000000 229 ns/op 4.4MHz

OutBitsMSBLoop 10000000 229 ns/op 4.4MHz

OutBitsLSBUnroll 10000000 221 ns/op 4.5MHz

OutBitsMSBUnrool 10000000 221 ns/op 4.5MHz

FastOutClock 100000000 11.3 ns/op 88.7MHz

FastOutSliceLevel 100000000 14.7 ns/op 67.8MHz

FastOutBitsLSBLoop 100000000 17.7 ns/op 56.6MHz

FastOutBitsMSBLoop 100000000 17.5 ns/op 57.1MHz

FastOutBitsLSBUnroll 100000000 12.3 ns/op 81.5MHz

FastOutBitsMSBUnroll 100000000 12.4 ns/op 80.8MHz

FastOutInterface 50000000 30.6 ns/op 32.7MHz

FastOutMemberVariabl 100000000 14.6 ns/op 68.5MHz

This test is run as part of the continuous integration via github.com/periph/gohci to be able to see any drop in the performance.

Conclusion

- Beware of the danger of micro benchmarks. They can give you an incorrect view

of the reality and make you optimize for the wrong things.

- 119MHz on a Raspberry Pi 3 is too good to be true.

- Optimizing for the wrong thing may be worse that not optimizing at all.

- Learn to love and fear the SSA optimizer, and its inscrutable entrails.

- The optimization process can be counter-intuitive at times.

- Reading and writing a digital I/O pin can have wildly different performance

characteristics.

- Don’t assume one is faster than the other, it varies across platforms.

- The difference between input and output performance can be as large as 8x. Benchmark accordingly.

- It’s not because one platform is faster at writing that it will also be faster at reading than a second one, as shown above with the Raspberry Pis.

- Loop unrolling is a useful technique but as all good stuff, it should be used with moderation.

- Interfaces may be costly, or may not. Benchmark.

- Same goes with variables in very hot path.

If you need MHz range performance, run the GPIO benchmarks provided by periph-smoketest and use the choose the right algorithm for your project.

p, ok := gpioreg.ByName("GPIO12").(*bcm283x.Pin)

if !ok {

// Either fallback to slow path or bail out.

}

// Call Out() at least once, to ensure the pin is initialized correctly.

if err := p.Out(gpio.Low); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

// Then use FastOut() to stay on the fast path:

p.FastOut(gpio.High)

On the other hand, reading is now optimized with no API change at all!

Happy bit banging!

Further research

Further improvements can build on top of this research to get closer to a high performance, glitch-free operation:

- runtime.LockOSThread() was tested and showed no visible

performance impact on any platform. On the other hand it could help with

jitter so it could be worth investigating in your specific context.

- Leverage OS process and thread priorities to mark the thread or process as high priority. See issue #185.

- Building upon the prior item, create a stable glitch-free 1MHz logic analyzer by leveraging bcm283x.ReadTime() for precisely timed sampling at 1µs rate on a multi-core system.

- Determine the source of the difference in reading performance for sysfs driver between the RPi3 and RPiZW.

p.s.: Did you find a factual error? An incorrect methodology? It happens! Or just excited about this research and want to discuss it more? Please join the #periph Slack channel (see top right of the page) to comment about this with the community!

Thanks for reading!

Edit this page

Edit this page